Meet The Maker: Julian Roche & the Golden Ratio

Meet The Maker: Julian Roche from Roche Cutlery

MTM #25 by Bjorn Jacobsen, September 2023

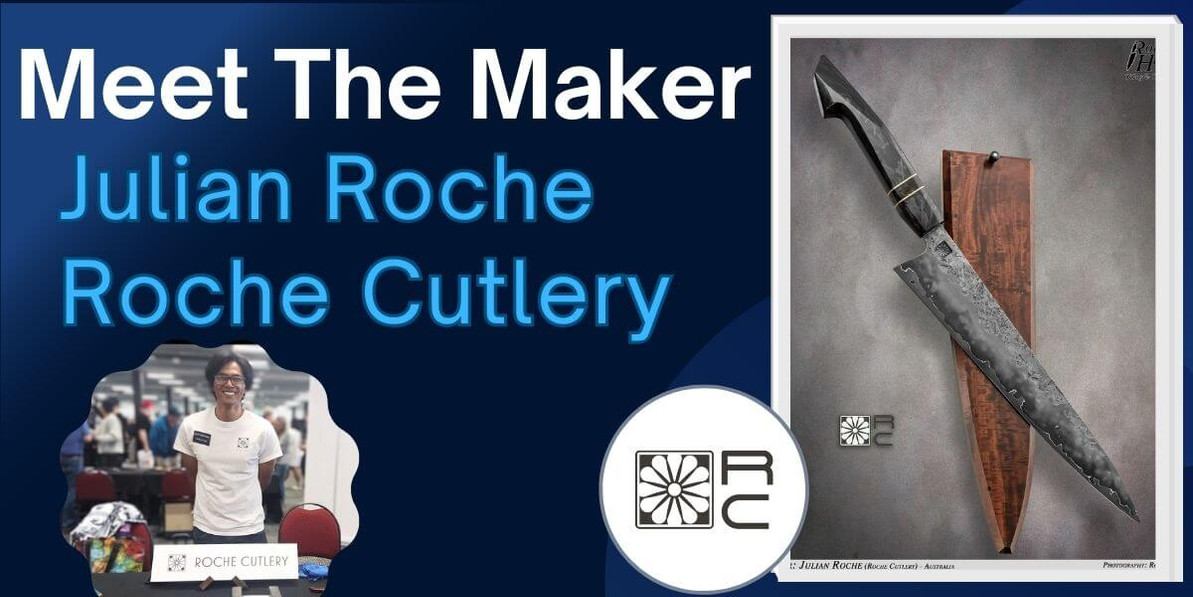

Julian Roche is a maker from Western Sydney really starting to turn heads in the Australian knifemaking community. Exhibiting this year at Sydney Knife Show for the first time, he had some amazing knives on the table. Julian also took home a trophy from the 2022 Australian Knife Making Awards in the Best in Show category. Here is a bit about his story as a maker and some photos of his work.

My origin story

I’m Julian Roche from Roche Cutlery. I am 31 years old and from Sydney.

I have always had the DIY spirit instilled in me since I was a kid from my parents. Both my parents are always resourceful due to us being an immigrant family. My parents would pick up broken furniture off the street and repair it for us to use at home. My dad doing the woodworking and my mum doing the upholstery. Naturally, this made me want to ‘help’, and both were happy enough to let me make a mess and enjoy the making world.

Slippery slope into knife makingI would eventually get brave enough to sharpen my dad’s knives, which of course led to me ruining a few of them. Through perseverance and the gnashing of teeth I did get to the point where I could make the knives sharper.

This was my first foray into the bladed world and naturally I wanted to try and make my own knife. YouTube was still in it’s infancy at this point (2009 maybe?) and there were only a handful of videos on knife making. For me to get any credible information I would jump onto the various American based blacksmithing or knife forums.

Making charcoal and starting fires

All this information and having access to other makers to ask questions and learn from online was like opening a pandoras box for me. Learning a lot but creating also all these new challenges I had not thought of before jumping in.

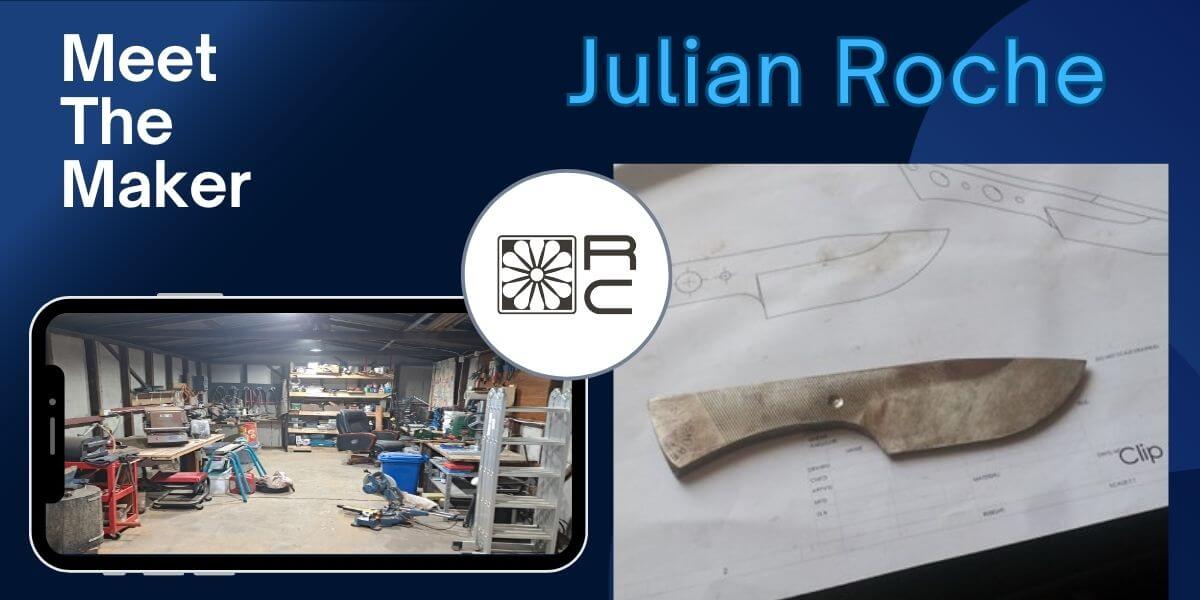

My first knife was made from an old file, this saved on heat treatment but meant having to deal with hardened steel straight away.

Then later I wanted to start actually hitting some hot steel to expand my skills. I built a charcoal forge, made my own charcoal, bought a cheap anvil and started going to town. Being young and having more energy than I knew what to do with, I did a little bit of everything. I handmade damascus, tried to smelt my own steel, did general blacksmithing and, of course, nearly set the house on fire on one occasion!

Uni and motorbikes

Around the time I started at Uni I also fell in love with motorbikes, and the freedom of road tripping. The passion for knife making went on the back burner for a while. Eventually this ended up being a six year hiatus from actually making knives but I never lost the love for it. I would keep myself entertained with youtube videos and dvds, books and magazines knowing I would come back to the anvil at some point when it felt right.

(My Yamaha XT660X on one of my many adventures to the middle of nowhere, this was on a journey across Tasmania back in 2016)

Covid and back into it

Eventually covid hit and I couldn’t ride my motorbike for anything other than work. As for many makers this created more free time at home and I wanted another hobby again.

The timing was right for me to take another, more serious, attempt at knife making and when getting back into it I decided this was something I wanted to do long term.

Specialising in Chef’s knives

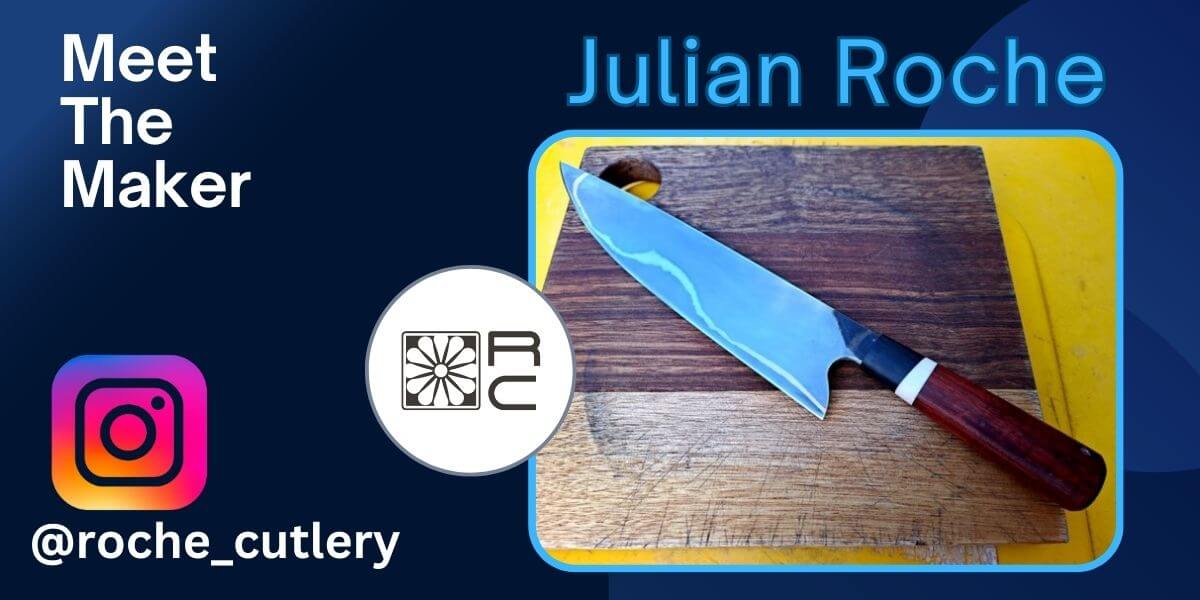

I decided to focus on chef’s knives as that was something either my parents or I would get the most actual use out of. I started with the more traditional or “practical” blade profiles and handle shapes. Over time as my confidence and skill levels increased, I have been able to focus more on the artistic side of knives to find my own style.

Back into knife making in 2021, CuMai chef’s knife with ebony, juma and bloodwood handle.

Creative influence – texture and finishes

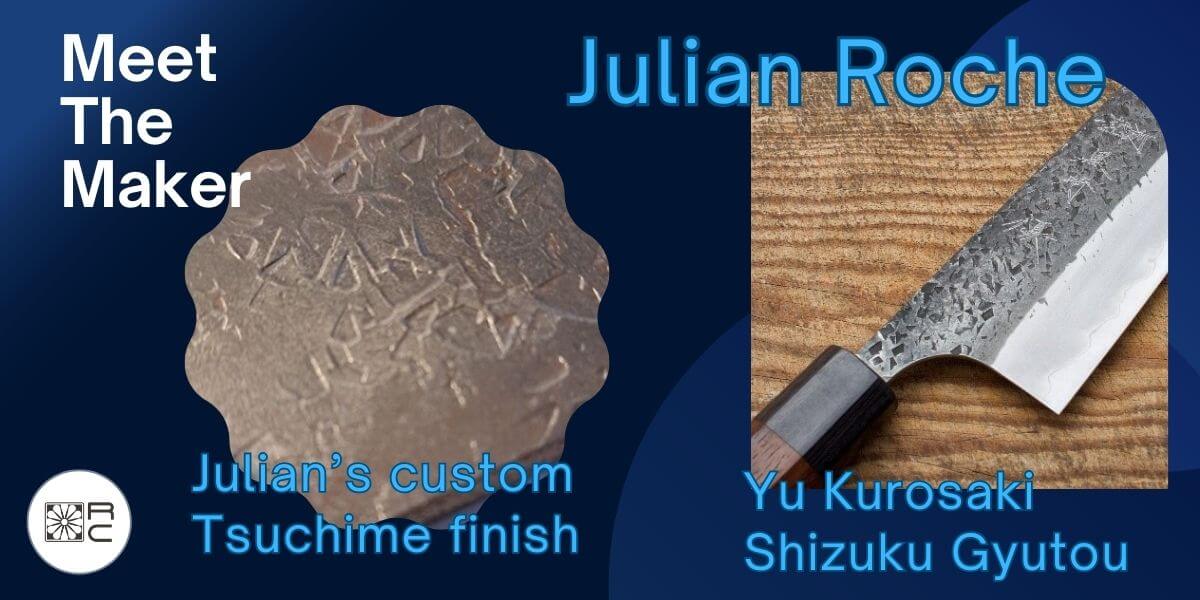

My own style is influenced from what I love in the work of other makers. Some of the ones I would like to give credit are Yu Kurosaki (LINK) for the creative tsuchime finish he does on his blades.

(Editor’s note: Yu Kurosaki is a Japanese Master Blacksmith – the youngest knifemaker in Japan to ever hold this title)

My original texturing hammer was based of his “Shizuku” and “Senko” range of finishes. Tsuchime is a Japanese hammered finish leaving a distinct texture considered to give a respectful nod to the handcrafting techniques of ancient Japan as well as to improve food release from the blade.

When it comes to shaping handles I am also inspired by Don Nguyen (LINK) for his minimalistic aesthetic and faceted handle design, influencing on some of my own knives with sharp, clear angles and facets. As well as Jelle Hazenberg (LINK) for his stellar handle sculpting and facet work. Both are makers I enjoy taking elements from into my own work.

All up – maybe 5 years and 50 knives

So far I have been making knives for maybe four or five years all up. Around two years when I was younger, and then when coming back to knife making a few years ago I have so far been going another 3 years or so.

In that time I have not actively been keeping count but I would estimate I have finished more than 30 knives and less than 50. If we are counting failures than probably double that number!

Hidden tang is my favourite

When it comes to blade or handle type, the hidden tang is my favourite. To my mind it is easier to get a nice pinch grip balance point when the knife is made this way. This is my preference for any knife I use myself and if done correctly, can make the knife feel almost weightless.

I also believe that

a hidden tang allows for complete creative freedom to shape the handle however

I like.

That being said, I make kitchen knives where handle strength isn’t at the

forefront. If ultimate performance is the goal, then a full tang with bolted

scales is most likely going to hold up better. But for my style of knives,

I believe the hidden tang construction is the right choice.

Complimenting skills

When Bjorn asked “Do you have a favourite area you like to focus on within knife making?” my answer is that you might want to look outside of knife making to improve also within knife making, if that makes sense?

As corny as this might sound, I just want to become a better maker in general. I have found the more knowledge or skills I learn overall, the easier I am able to push my creative limits also within knife making.

To me as a maker it is essential to pursue different avenues of the creative

process to become a better maker within any one field.

I think that to design good looking knives you need to have a solid foundation of design and colour theory, as well as some drawing skills.

In a more practical sense, you need to know the correct order of operations as well as some machining knowledge. This helps to grind and finish your blade and handle and keeping the crisp lines in the finished knife.

The Golden Ratio and functional art

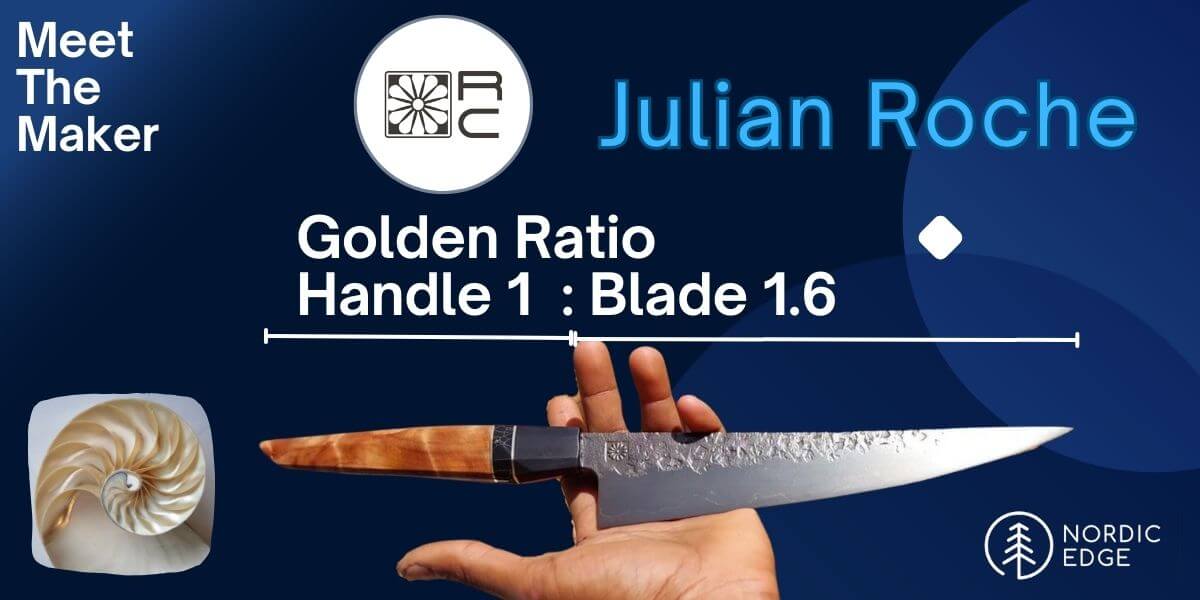

I find the hardest thing to do is trying to balance performance and art. I try to make my blades as physically and visually balanced as possible, with my personal rule being to follow the golden ratio of handle to blade.

The golden ratio is approx. 1:1.6 and as applied to knife making it means the 1 being the handle size and the 1.6 being the blade length. This ratio works on a visual level for most knives from about 200 mm onwards. There are certain tricks with lines and angles you can play with to make the blade or handle seem longer or shorter than it, is but I think the golden ratio is a great starting point.

Knife balance

Getting the knife’s weight physically balanced can be harder to achieve and requires a bit of back and forth grinding. I will usually get my profile done and bevels roughed in, then get my handle dimensions roughed in as well.

Once I have my handle design roughly shaped out, I’ll check the balance point and modify either the handle or blade to adjust accordingly. All while trying to keep the original aesthetic and design flow.

The last part is always the hardest

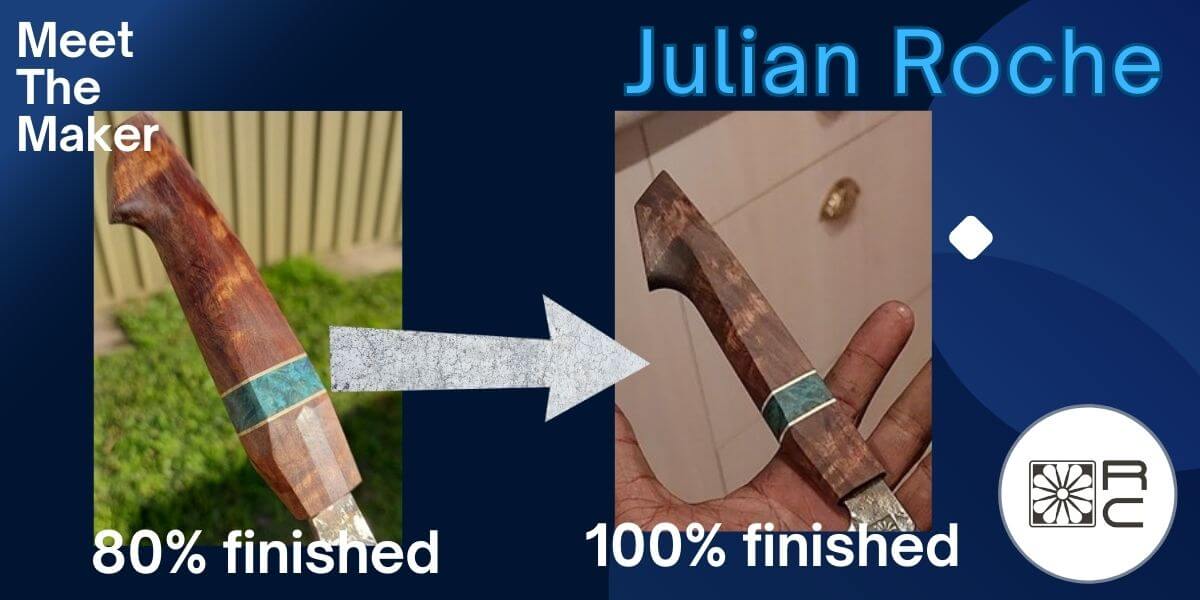

There comes a point in my making process when I get to about 80% completion, and I can see the final product start to take shape. It is usually the point in my process where I can finally recognise the object as a knife rather than a piece of steel and a block of wood.

This is the point in my process where I slow down and evaluate everything. I test the blade geometry, the weight, the balance and the feel of the knife. Most times I need to go back and dial everything in little by little, but it brings me such joy seeing it come closer and closer to what was just a figment of my imagination – now coming to life.

Handle at final dimensions on the right. Did tweaks after testing ( left photo), found it to be a bit too bulky and handle heavy. Adjusted for more weight near the pinch point and a more slender profile.

Some of my favourite things

1084 steel is by far my favourite steel to work with. It is not the most high-performance steel out there, but what it lacks in extreme performance it makes up for in versatility. It can be forged, and heat treated very easily - and it is the staple for modern damascus steel. If I had to be limited to a single steel, 1084 would be the one.

Gidgee and carbon

fibre are my favourite handle materials to work with. Gidgee is an amazing

timber; it is beautiful, doesn’t need stabilising, takes an amazing polish and

is so incredibly tough in use.

I love the way carbon fibre looks when it is clear coated and polished; it has

a high chatoyant shimmer in the sun that very few other materials can come

close to. I do not enjoy working with it as it is an itchy mess that will ruin

your lungs, but some sacrifices must be made for beautiful results. (Editor’s

note: Meaning a bit of itching, Julian is not saying to grind carbon fibre

without a proper dust mask :)

My maker goal: honayaki Yanagi-ba

My big knife making goal is making a honyaki Yanagi-ba knife. While not as flamboyant as many knives out there, it is one of the most technically demanding knives to make. It is a long single bevel blade with a hollow on the back. Traditionally they are made with a hardenable steel core clad with a single soft outer cladding. This usually means warping in the quench..

Skilled makers will add an initial pre-bend in the blade before heat treatment causing the blade to warp true out of the quench.

Additionally, during the grinding, the blade will continue to warp as steel is removed. Managing all the warping and twisting, whilst trying to keep the geometry correct and bevels true is, I believe, the ultimate test of the maker’s skill within my area of interest.

Adding the next layer of difficulty would be the ‘honyaki’ factor. Honyaki is a term associated with a mono-steel blade with a hamon, which, in of itself, is an incredibly demanding task. But added to the above factors takes the difficulty to the absolute extreme.

Knife making as creative outlet

Knife making is a passion hobby of mine. It is a creative outlet for me that I simply don’t get anywhere else in life. It is, in fact, harder on my body than my day job, both mentally and physically, but I do it purely because I love it. If I need to de-stress or relax, I usually spend time in the garden, cook, detail my cars, read a book or play games.

3 tips for anyone starting out

Firstly, I would say get the groundwork sorted out first. Learn the basics and learn them well. Don’t try and start making a sword as your first thing. Start small and work your way up. The “goldilocks principle” is a good guide, we enjoy projects more when they are challenging - but not so far out of your current skillset that it becomes too frustrating to continue.

Once you have the basics down, then you should focus on the finer details. Balance, proportions, fit and finish, etc. The finer details can take your knife from average to spectacular very quickly.

Learning basic artistic principles will help you design better knives. No, you don’t need to be an art major at all, but you need to, I feel, learn the basics to help get a better understanding of certain aspects of knife design. Especially if you want to branch out and experiment with outlandish designs or colour combinations.

Finally, I would say just get in the shed and do it. Life’s too short not to try out something you’re passionate about or have an interest in. There are always day courses if you’re unsure whether you want to commit the resources to this hobby, but there shouldn’t be anything stopping most people from at least giving this craft a go!

To follow Julian’s work on Instagram: LINK

Photo credit: Rod Hoare Knife Images

Recent Posts

-

The Etch Test: Ferric vs Hydrochloric vs Gator Piss

The Etch Test: Three Very Different Looks From One Steel One of the great things about knife making …3rd Jan 2026 -

Why Bed The Tang In Epoxy - Then Knock it OFF Again.

What is "Bedding the tang"? Bedding the tang means gluing a stick-tang blade into the handle block i …21st Mar 2025 -

Marble Leather - How to Dip Dye Veg Tanned Leather

This was my first experiment with hydrodipping or dip dying leather, and it came out pretty cool! I …14th Mar 2025